'The functioning, but unrecognised, government of Somaliland, which wants to secede from the near lawless Somalia, will be encouraged. A new pragmatism could be the way ahead''. Ex President Thabo Mbeki

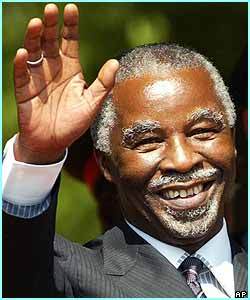

- IN THE study of his home in Johannesburg, surrounded by books and ignoring the cricket on the giant screen facing his desk, Thabo Mbeki makes a point about Africa. He argues that in the past decade, the continent went from being firmly placed on the global agenda to being inexplicably removed from it.

The former president is famous for not being one of life’s gesticulators, but during a recent interview he looked as though he took this issue — of what he perceives as Africa’s relegation— quite personally. When he was president in the early 2000s, Mr Mbeki was a driving force — arguably the driving force — in getting Africa a seat at the high table of world affairs for the first time, and actually being listened to.

The problem in eastern Congo is one of nationality and in Mali and neighbouring countries it involves the Tuareg and Berber peoples, Mr Mbeki says. In both cases the issues are long-standing and the dispatch of peacekeepers for a couple of years would not resolve them.

"What is it that we did or did not do that resulted in what I think is a major retreat, in terms of the disappearance of the position of Africa?" Mr Mbeki asks. "Africa needs to address that."

His question remains unanswered, as there was no time to explore it further. But one piece of evidence which he advanced in support of his thesis is the case of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (Nepad), which he helped to found in 2001-02.

Its mission was, and remains, to get Africa and its people working in a modern way and to help attract and harness the hundreds of billions of dollars of investment required to build infrastructure. The high point for Mr Mbeki’s pro-Africa policies probably came in the Canadian town of Kananaskis in 2002 when the Group of Eight (G-8) wealthiest nations adopted an action plan to help lift the continent to growth and prosperity.

In the same year, African leaders wound up the discredited Organisation of African Unity (OAU), a trade union of dictators, as the late Julius Nyerere of Tanzania once called it. They launched the African Union (AU) in Durban, presenting it as a fit-for-purpose replacement that would do on the political front what Nepad was doing with its socioeconomic programmes.

"We had the situation that the African agenda came to assume a much higher profile on the global agenda," Mr Mbeki recalls. "There was much greater focus by the whole world, a sense of ‘what must we do to support the Africans’.

"That’s gone. I think there’s been a major retreat as far as that’s concerned…. When the

G-8 went back to Canada in 2010, their own G-8 action plan was not even mentioned."

Not everyone will agree with Mr Mbeki’s portrayal of an Africa mysteriously marginalised once again. Some will say there has been an inevitable change of focus in Europe and North America as countries try to fight their way out of recession. Others may suggest that he is reducing Africa’s interests to those of a costly panoply of pan-African institutions whose importance he exaggerates.

It can also be argued that Africa’s place in the world today is more established and its objectives better understood. After all, G-8 summits now have a rotating presence of leaders from the developing world, including from Africa.

Public and private investors led by China have migrated to the continent during the past 10 years, snapping up natural resources, building infrastructure and servicing a new middle-class. SA is pretty much a fixture at key international gatherings and last year it joined Brazil, Russia, India and China to change the potentially powerful Bric economic group to Brics.

Someone less understated than Mr Mbeki might claim a share of the credit for those changes.

A spry 70, Mr Mbeki and his small staff are keeping busy. The dog days of 2008, when he resigned as president after the African National Congress (ANC) "recalled" him, are drifting into the past.

They will always be part of his history, like his roundly condemned views on HIV/AIDS and his refusal to confront President Robert Mugabe over human rights abuses. But also part of his history is his best known presidential speech, "I am an African".

These days, Mr Mbeki tends to keep his views about domestic politics to himself. He did not attend the ANC conference in Mangaung, because he was dealing with African business in Addis Ababa. As the AU mediator on Sudan and chair of the Economic Commission for Africa’s panel on illicit capital outflows from the continent, he has his hands full.

After decades of conflict, Sudan split into two countries last year when the south became independent. The first two years have been bumpy, largely because of a dispute over sharing oil revenue.

Mr Mbeki is not in favour of the AU scrapping its policy that member states must stick with the borders they inherited from colonisation. "I don’t think we should change that or we could get ourselves into a lot of trouble," he says. "You will just introduce an extraordinary level of fragmentation."

He makes an exception for Sudan because both sides tried to make their union work under a peace agreement they signed in 2005. They failed and he felt it was right that they be allowed to go their separate ways.

"If countries, without use of force, without compulsion, voluntarily agree (to part), there should not be prohibition, like a heavenly decree," he says. "No, that should not be the case."

The functioning, but unrecognised, government of Somaliland, which wants to secede from the near lawless Somalia, will be encouraged. A new pragmatism could be the way ahead.

Mr Mbeki has over the years mediated in numerous crises, from Cote d’Ivoire to Zimbabwe. The results have been mixed and he is noncommittal when asked if we are witnessing a potential resurgence of major conflicts in Africa — in Mali and eastern Congo — contrary to the mellow script written by investment advisers. "I don’t know," Mr Mbeki says.

"But one of the things the continent must do is to say we have got to go beyond fire-fighting. We need prevention of conflict, early warning systems and so on."

The problem in eastern Congo is one of nationality and in Mali and neighbouring countries it involves the Tuareg and Berber peoples, Mr Mbeki says. In both cases the issues are long-standing and the dispatch of peacekeepers for a couple of years would not resolve them.

"The continent should say, ‘Is there trouble brewing somewhere?’ … I don’t think it’s very difficult to foresee some of these big conflicts," Mr Mbeki says.

Origin:

No comments:

Post a Comment